"I think that regardless of the political situation, decision-makers and communities need reliable and trusted information to make decisions. It is easy to think that it is something that is necessary in a democracy model, but reality, it actually is something necessary everywhere."

By Katherine M. Condon, Ph.D., Interview Editor - SJIAOS

Ms. Nancy McBeth has been a member of the International Association for Official Statistics (IAOS) Executive Committee for the last six years and currently is the Advisor to the IAOS President. She began her career and interest in official statistics in her native country of New Zealand, where she spent over 25 years at Statistics New Zealand. There, Nancy undertook a number of operational and senior management roles with Statistics New Zealand; including leadership of the 2006 New Zealand Census. Following the 2006 New Zealand Census, she served as a technical advisor to the Statistics Centre Abu Dhabi (SCAD). Currently Nancy is a Consultant with the Statistical Centre for the Cooperation Council for the Arab Countries of the Gulf (“GCC Stat”), based in Muscat, Oman. Her particular responsibility and interest as a consultant has been on population censuses.

Nancy's qualifications include an MA in Political Science with a BA in Mathematics.

INTERVIEWER: Thank you so much for allowing us to interview you. Let us start at the very beginning and go back to your childhood in New Zealand. What was it like growing up in your country?

I grew up in a multi-generational family of migrants. Both my parents had migrated to New Zealand from Scotland, though at different times. That meant that apart from our beloved grandfather who shared our family home, our immediate family did not have many close family members living nearby. Partly because they were from Scotland, both my parents had a strong love of education. Even though neither of them had done very well through the school system, they both had a great love of reading. So, we had lots of books at home and our parents encouraged us to do well in school.

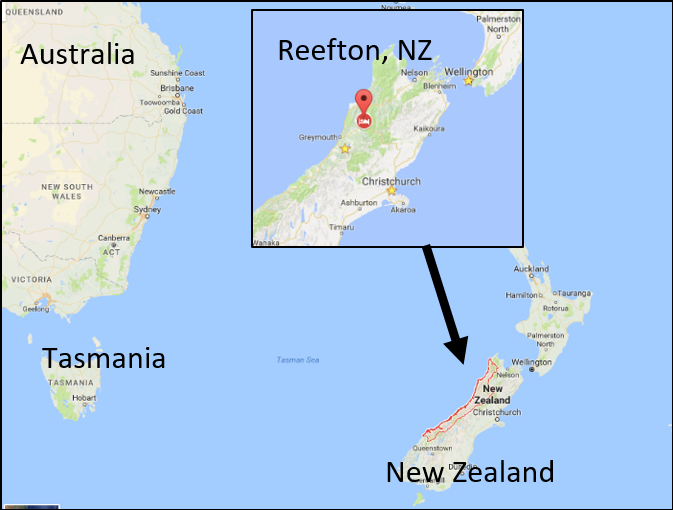

Reefton[1], the small country town where I grew up, is on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand. It gets a lot of rain -about 2000 mm of rain per year [or about 79 inches per year]. It can be tropical, but also has cold winters with frost and sometimes snow. That means, that although we got a chance to do a lot of outdoor activities – such as taking dogs for walks and going out hiking with friends and other outdoors activities – it also meant that we spent many weekends indoors. Reading was a very important to pass the time as a child. It certainly gave me a good basis for future life.

Reefton[1], the small country town where I grew up, is on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand. It gets a lot of rain -about 2000 mm of rain per year [or about 79 inches per year]. It can be tropical, but also has cold winters with frost and sometimes snow. That means, that although we got a chance to do a lot of outdoor activities – such as taking dogs for walks and going out hiking with friends and other outdoors activities – it also meant that we spent many weekends indoors. Reading was a very important to pass the time as a child. It certainly gave me a good basis for future life.

INTERVIEWER: What was your education like before university?

In most of New Zealand, there is a good government school system and I went to the local schools. We had a small country primary school – equivalent to “elementary school” in the United States. This brought in kids from some of the surrounding farming areas. After that, I went on to the local secondary school as well.

I was one of those kids who really enjoyed school. I discovered quite early on that I was quite good at Maths, as well as some other subjects. We had good teachers, especially at secondary school. These teachers weren’t just from New Zealand, but from other parts of the world (U.S., U.K. for example) as well. When I was growing up, the school system for teachers meant that they had to do something called “Country Service.” Teachers had to do two to three years of service in a country town. As a consequence, country schools had a wide range of teachers. We were also streamed academically - in our case given the size of the school, classes had an “A-stream” and “B-stream.” In my year, the A-stream had 30 kids - with two-thirds girls and one-third boys. I think that, and research seems to support this, that the style of teaching when I was in school seemed to serve girls better than boys. But it meant that I grew up thinking that girls could indeed do anything because we certainly excelled academically. It may seem strange to some people now, but it wasn’t until I got to university that I discovered there were lots of young men out there who were actually interested in academic subjects. I hadn’t seen this growing up in my small country town environment.

One of the other things for me was, because I went to a small country town school, there was some subjects in which there weren’t teachers for the subject. So, we just did those subjects, in those days, by remote learning through the New Zealand Correspondence School[2]. I guess in today’s version, it would be done by sitting down in front of one’s tablet computer using the internet. However, in my day “correspondence” was done through a mixture of radio[3] and assignments that came by mail. So, we would wait for the mail to come with the graded assignment and to see how well you had done.

In my last year, there were only two of us in the class and we did all of our subjects by correspondence. Fortunately, we (my colleague and I) had a conversation before and agreed that we would do the same subjects. This made it easier for us. We were able to help each and bounce ideas off each other. It did mean that we did learn very good study habits. By the time we went to university, we had developed very good independent learning habits. We were very used to learning on our own and did not need to have a teacher supervise us.

In addition, living in small country towns means you take on leadership roles. For example, I was Head Girl of the school in my final year.

INTERVIEWER: Looking back to our childhoods, we often find that a particular event or person had an impact on our later years. Did a particular person or event shape you into the person you are today?

My parents were very community-minded and despite limited formal education they took on leadership roles in different community organizations. When I think back on it now, that experience of assuming people will contribute to the community for the greater common good certainly shaped some of the things that I have done. This includes volunteer work with community organizations and local government in New Zealand, or more recently my involvement with the IAOS.

New Zealand and Australia share a very important day – April 25th - ANZAC day[4]. It commemorates the involvement of Australian and New Zealand troops in the Gallipoli campaign and the invasion of Turkey in 1915, during World War 1. Now the troops didn’t actually have a successful invasion of Turkey, but that campaign shaped New Zealand and Australian sense of independence. Although we were independent politically, we still were strongly influenced by Britain. So, one of the things about that is that every year now in New Zealand and Australia you see people gathering at dawn and then later in the morning to commemorate the veterans and acknowledge this shared part of our history. There are also community services, with guest speakers. My parents were both heavily involved in what New Zealanders call the Returned Services Association – similar to the American Legion in the United States. This meant that when there was an ANZAC Day guest speaker from out of town or even, sometimes, out of country, my parents would host the guests for breakfast. I learned a lot about the bigger world and realized as a child that the world didn’t just end at the boundaries of our town or even our country. Many of the people I went to school with didn’t have those same experiences. So, when I think back on it, I think it was a combination of those things – the community spirit as well as being exposed at a young age to other people who had other experiences.

INTERVIEWER: Your CV states that you have a BSc in Mathematics from University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand and a M.A. Honors in Political Science also from University of Canterbury. How did that come about?

I think it was pretty evident when I was in school that I was going to be the first person in my family to go on to university. The teachers encouraged my parents that this was a good idea. I too realized that this was a good way out of a small town. While a small town was a nice place to grow up, it was not where I wanted to be permanently. When I finished secondary school, I thought I wanted to become a maths teacher, because I really enjoyed maths. So, I went off to university to do a maths degree. Early on in my degree I developed a friendship with someone who was doing a degree in political science. Thanks to her, I discovered a whole new world of subjects in university. I was able to do some political science papers as part of my BSc. At the end of this degree, I decided I wasn’t quite ready to become a maths teacher and so went on to do my MA in Political Science.

This was an exciting time for New Zealand, as the country diversified its economy and moved away from a reliance on agricultural exports. My master's thesis was on the role of exporting incentives in diversifying the economy. These incentives were provided to businesses who were looking to export non-agricultural products. The thesis required me to use some of the maths skills, as well as my interest in politics and some of the economics that I had also studied at university. The thesis also required me to use statistical data and econometric modeling for the time. While some of the statistical data was from published sources, I also needed trade data from Statistics New Zealand. During the early 1980s, government departments had just started this process of the user pays for government services. This meant that if you wanted some non-standard government services, you needed to pay. In the case of the Statistics New Zealand data, this meant paying for trade data. So here I was as a masters student, [an economically] poor student, but I paid from my hard-earned cash to then New Zealand Department of Statistics for some of their trade data and showing my age, I entered this data into punch cards.

[A slight break in the conversation here as we both laughed – myself, as a child I wrote stories on IBM punch cards. Nancy continued to say that until very recently she kept many of the punch cards of data to the amusement of her husband. Nancy added that it was just a couple of days before this interview she had heard that one can still buy punch card readers on eBay, but that it would cost about 20,000 USD.]

I guess that this could be called my first introduction to official statistics. I had to actually buy some data to study.

I asked Nancy if she also had used paper tape for data analysis. She recalled that she had a couple of holiday jobs in which she had to use paper tape. However, these experiences led her to realize that she wasn’t cut-out to be in the IT industry. However, we both agreed that these experiences with punch card data entry and paper tape gave us an intimate knowledge of the physicality of data which is not apparent today when one can just pull data off the internet without entering and cleaning it. She agreed and added that in those days, you had to think really hard about

- what is it that I really want;

- how do I want to code it;

- how am I going to use it.

In the early 1980s, the whole world of computing was really just starting to open up. Entering and processing the data for my thesis was a real introduction to this world. One also had to question whether one had the right skills to do things, like analyzing data and presenting the findings. This meant you also had to actively manage the data, including understanding the structure, the sources and what the data might mean. This is different from today where one is able to take tables and data off the web and you have no idea where it might have come from and how it got to the web.

There is a little bit of irony in this, because when I met my prospective in-laws, I discovered that both had worked for the Customs Office AND were responsible for the trade data that I used in my thesis. So, it gave us all something else in common.

This is a preview of an interview conducted for and published in the Statistical Journal of the IAOS. The full interview can be read here.

[1] Reefton was originally a gold mining town. It was the first town in the southern hemisphere to be lit by electricity. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/keyword/reefton.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Correspondence_School.

[3] Nancy said the radio is how she learned her “really bad” French pronunciation.